* Notes *

* Notes *

My review of Oakland Opera Theater's Uksus up on KQED Arts.

* Tattling *

People next to me and behind me took photographs and videos of the opera, heedless of the sounds their devices made.

Reviews of Performances and their Audiences

* Notes *

* Notes *

My review of Oakland Opera Theater's Uksus up on KQED Arts.

* Tattling *

People next to me and behind me took photographs and videos of the opera, heedless of the sounds their devices made.

THE DO LIST

By Charlise Tiee Sept 1, 2016 | Updated Jan 11, 2024

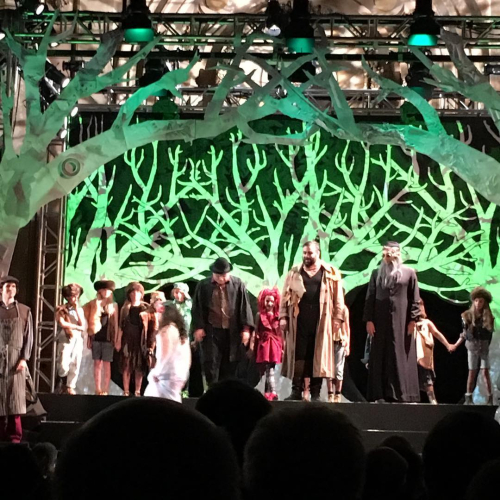

A scene from Act III of Erling Wold’s ‘Uksus’ as performed by the Oakland Opera Theater. (Photo: Oakland Opera Theater)

Opera is a difficult business. So much can go wrong. Even if you have a fine composer, excellent musicians, a strong conductor, and seasoned singers, success is often still highly elusive.

Such, regrettably, is the case for Uksus (“Vinegar”) by composer Erling Wold. The chamber opera is based on the life of surrealist writer Daniil Kharms and the short-lived but influential 1930s Soviet avant-garde collective OBERIU. It’s the latest production from the newly resurrected Oakland Opera Theater (OOT) at Oakland Metro Opera House, a capacious and multi-faceted black box theater near Jack London Square that also hosts metal shows and underground wrestling matches.

Bay Area composer Wold is known for his chamber operas. The first of these, A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil, brought him to the attention of OOT in the 1990s.

Wold’s musically-captivating if theatrically disorienting Uksus, which premiered in San Francisco in 2015 to lesser acclaim than his previous opera, Certitude and Joy, has been revived here with much of the same cast and crew. The only notable exception is the replacement of Duncan Wold (the composer’s son) in the role of Pushkin — Kharms’ used the famous Russian author’s name as an alias.

The music, performed by a small, agile orchestra neatly conducted by Bryan Nies, is a captivating mixture of minimalist arpeggios coupled with jazz. There’s also a little Eastern European styling thrown in for good measure. The talented cast, which includes the inimitable soprano Laura Bohn as Fefjulka and the rich-voiced mezzo Nikola Printz as Our Mama (and in the last act, Stalin), performs the work’s many duets and trios with precision and passion. Tenor Timur Bekbosunov handles the title role capably and flamboyantly.

Unfortunately, the staging of the opera, directed by Jim Cave, doesn’t match the memorable music. The gimmicky feel of the mise-en-scene begins as soon as you entered the venue, with Soviet border guards ordering patrons about, demanding passports and creating a sense of havoc and confusion. We see Pushkin resting on a stretcher. Funeral rites are performed. Another performer declares himself to be a samovar, and gives us a brief sketch of Kharms’ life before ushering us into the house.

This pre-performance charade sets the tone for the evening — one that’s absurd and not just a little pretentious. The cast attempts to hold our attention by surrounding us and making eye contact with individuals. One performer even aggressively tried to sweep my feet away from under me with a broom on opening night when I saw the show. Yet the piece lacks enough to grasp onto as far as drama goes. It dissolves into simple spectacle.

Though the plot goes through points of Kharms’ life as a children’s writer, husband, founder of OBERIU, and psychiatric ward prisoner, Wold doesn’t do enough to flesh out his main character. Instead, we get a wacky discourse on meatballs (the dish is apparently what the piece is about, according to a line in Act II), an enormous puppet robot, and dodge balls thrown in our direction.

This uneven production comes off as an ambiguous sign for the daring and gritty little Oakland Opera Theater, best known for mounting the well-received west coast premiere of Philip Glass’ Akhnaten in 2004. The company all but disappeared in 2009, going from two opera productions annually to one every two years.

The company’s progress has been hampered in part by real estate woes. It has had to move twice in the last decade. But it’s forging ahead nonetheless.

Next up, if OOT manages to sort out a dispute with one of its current neighbors, the organization plans to stage a collaboration with Tourettes without Regrets, poet Jamie DeWolf’s monthly genre-defying performance art show also at the Oakland Metro. The project is a Romeo and Juliet opera featuring audience participation. Unlike Uksus, hopefully the “immersive theater” elements next time around won’t stand in the way of the music.

Uksus plays through Sunday, Sep. 4 at Oakland Metro Opera House in Oakland. For tickets and information, please click here.

This article was originally published on https://www.kqed.org/arts/12004739/oakland-opera-theater-reemerges-with-musical-if-gimmicky-uksus

* Notes *

* Notes *

My review of San Francisco Choral Society's Requiem by Verdi is up on San Francisco Classical Voice.

* Tattling *

The adolescent girl (who was there with her little brother and their mother) in front of me in Row H of the Orchestra level, had a seat for her purse that was full of cellular phones and a big bouquet. She took many selfies as we waited for the performance to begin.

The children behind me ate candy doled out in plastic bags during the entire performance. This was evidently to bribe them to stay occupied and silent as their mother sang. It was effective except that the bags rustled at times but I must be getting more tolerant or nicer or something, because it didn't really bother me that much, if at all.

* Notes *

* Notes *

West Edge Opera opened its 2016 festival with The Cunning Little Vixen last night at the abandoned 16th Street train station last night in Oakland. While the orchestra could have been crisper under Maestro Jonathan Khuner, the beauty of Janacek's score comes through. Pat Diamond's production has a ton of charm and the singers did well.

In a time when there's so much awful news, it's easy to want to find an escape, whether it is the latest iteration of a blockbuster movie franchise or Pokémon GO. But what West Edge Opera has achieved here with Janacek's lightest opera represents more than mere distraction from the headlines, a refuge of sorts. The piece is a beautiful meditation on the cyclical nature of life, and though certainly sad, is also celebratory.

The reduced score by Jonathan Dove was played by a tiny orchestra of only 16 that made an impressively huge sound, sometimes overpowering the singers. There were intonation issues, but lots of spirit. Volti Chorus and Piedmont Children's Chorus looked and sounded great as well. The children are ridiculously cute.

The storybook set (pictured above) is also teeny-tiny, with an attractive forest motive that could be projected on with images of ferns, bark, brick, and even a deer head. The lighting, especially the shadows, looked quite evocative of a forest near an urban space with the gorgeous decaying train station walls. The staging is lively, and no one seemed constricted by the lack of space. The costumes are cute and not slavishly descriptive, the chickens wear yellow tutus, nary a feather in sight, but it is completely clear who and what they are.

The one misstep was perhaps the Dragonfly, a dancer in ribboned dress who flitted around between songs. Though her choreography was fine, and she managed to navigate the small space without running into anything or anyone, the dancing did not add much to the performance and seemed gratuitous.

Baritone Philip Skinner sang the Forester with warmth and humanity. Amy Foote is a piquant Vixen, her icy voice is nice and light but pierces through the orchestration. She has a lovely control of her instrument. Nikola Printz (Fox) sang with power and also has a slight strident quality that works for the role.

Joseph Meyers (The Schoolmaster), Nikolas Nackley (The Parson), and Carl King (Harasta) contributed fine performances, rounding out a strong cast.

* Tattling *

The couple behind me talked at full volume for the beginning of the first and third acts.

* Notes *

* Notes *

West Edge Opera's 2016 festival continued at the Oakland 16th Street train station Sunday afternoon with Powder Her Face. Maestra Mary Chun conducted Thomas Adès' chamber opera with precision. The production from Elkhanah Pulitzer is characteristically racy but somehow does show a little compassion for these very unlikable characters as well.

The music by Adès is a study in extremes, lots of highs and lows in the vocal lines. It seems very punishing and complicated. At times I found it pretty harsh, but the four singers were massively impressive, and all sounded and looked great. No one was drowned out by the orchestration, even though the musicians were loud, perhaps because we were on the same level as the orchestra and the acoustic of the station is not particularly suited to opera.

Before the performance it was announced that baritone Hadleigh Adams had a tickle in his throat, but it was hard to tell, his singing was strong. He had lots and lots of very low notes and rather high ones, and somehow reached them all with seeming ease. Soprano Emma McNairy also sang with power and nonchalance, hitting all sorts of notes in her upper register without simply sounding like a squeak toy.

Soprano Laura Bohn was a fine Duchess, terribly heartless in the beginning and startlingly vulnerable in the end. I was not expecting to feel sorry for her, but somehow the music and production came together nicely here.

Pulitzer's staging involves nudity, pink lighting, and wigs changed on stage, all elements we saw in her Lulu last year. She even wore Emma McNairy's platinum bob during the curtain call. But it all fit, and it is even clear that the composer himself was influenced by Berg, so it did make a certain sense. The set is simply a hotel room (Number 69, no less) with a sandbank on one side of the floor next to the bed. At one point sand falls onto the stage, the sands of time, doubtless, and the Duchess grasps at it helplessly, certainly the most striking image in the production.

* Tattling *

I was surrounded by opera lovers that were all fairly quiet, though the man to my left might have fallen asleep for a few minutes during the middle of the first act.

* Notes *

* Notes *

Conrad Susa's Transformations was performed by the Merola Opera Program at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music last night. Neal Goren conducted the jazz and pop influenced score with aplomb, the music sounded idiomatic. The production from Roy Rallo was very consistent with his style.

The piece is based on ten poems by Anne Sexton, from her book also entitled Transformations. The work consists of re-tellings of Grimm fairy tales, which are already rather dark, and take on an even more sinister meaning here Sexton is wry and very disturbing. Susa's music spreads the lines between eight singers who sing up to thirteen characters a piece. There's a surprising amount of singing together, which is quite nice.

Rallo's production is not, as far as I could tell, in a psychiatric hospital, its normal setting. Act I used only the downstage, everything else hidden behind a white curtain, and looked to be someone's living room with white Rococo style couch and cabinet, with a pink kitchen area stage left. In Act II a cave of grey plastic is revealed, and the couch turned around. As in Rallo's 2011 Barbiere for Merola, there was a lot of tinsel used. Tinsel stands in for Rapunzel's hair and for Rumpelstiltskin's straw spun into gold. The direction had a fair amount of slap-stick to it, a whole apple held in the mouth of Snow White to signify the apple stuck in her throat (pictured above, photograph by Kristen Loken) and straw thrown at the head of the miller's daughter.

The chamber format of the opera and its many parts makes it a good fit for Merola. Unfortunately lead soprano Shannon Jennings, who plays Anne Sexton, was ill. She did remarkably well in Act I, though sang with some strain. Her part was taken over in the pit by Mary Evelyn Hangley, but Jennings continued on stage, acting and mouthing the words.

Soprano Teresa Castillo was a game Princess and Gretel. Mezzo Chelsey Geeting as a plush, lovely sound as the Good Fairy and Witch. Tenor Boris Van Druff was very creepy as Rumpelstiltskin. Also impressive was baritone Andrew G. Manea as Iron Hans.

* Tattling *

The audience was fairly quiet. There was noticeable attrition after the intermission.

ARTS & CULTURE

By Charlise Tiee Jul 1, 2016 | Updated Sept 19, 2024

Members of the Bay Area-based chorus Cappella SF and composer Lisa Bielawa in a cell block on Alcatraz, the setting for Episode 9 of Bielawa’s new serialized made-for-video opera, ‘Vireo’ (Photo: David Soderlund)

Alcatraz has been the setting of many Hollywood blockbusters from Escape from Alcatraz to The Rock. But a serialized, made-for-video opera? Now that’s surely a first.

On a recent evening in June, the former federal penitentiary was the site of a film shoot for Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser — a 12-episode opera created by Bay Area native composer and musician Lisa Bielawa in collaboration with playwright Erik Ehn and director Charles Otte. On set for Episode 9, a chorus of vocalists sang out a dirge-like lament accompanied by hurdy gurdy from one of the cell blocks. Down the corridor, in the decrepit prison hospital, a string quartet played along with the sound of bells. Meanwhile, in a third room, a straightjacketed teen girl with a skull scepter confronted her doppelgänger.

The unusual project is being filmed in 10-to-12 minute episodes — perfect for the ever shortening attention spans of a new generation. Shot in Southern California, New York, and San Francisco, the series will be broadcast next year on public television and online, and seeks to bring opera to a broader audience by using a digital streaming model a la Netflix and Amazon.

Vireo follows the convoluted adventures of the titular character, a teenage girl played by 18-year old soprano Rowen Sabala. The young woman hears and sees things, and is ultimately accused of being a witch. She exists simultaneously in contemporary Sweden, 16th century France, and the Vienna of 1893, and is, apparently, possessed by a witch, played by the blind mezzo-soprano Laurie Rubin.

Recasting stories of female hysteria

Bielawa is best known as the long-time vocalist for the world-renowned Philip Glass Ensembleand, locally, as artistic director of the precocious San Francisco Girls Chorus. She grew up in the Bay Area and has also undertaken ambitious projects locally, such as a work she composed for massive musical forces at Crissy Field.

The origin story of Vireo goes back to the composer’s time as an undergraduate in literature at Yale, where she wrote a senior thesis about studies by men of female hysteria. The topic haunted Bielawa, and she collaborated with Ehn on a traditional three act opera in 1994. “I sent him stacks and stacks of photocopies of primary source material from several centuries,” says Bielawa. “He wove it all into a libretto with the name Vireo.” (Vireo is a type of songbird.)

Bielawa shopped the piece around to opera companies throughout the country, but came up short. The project was shelved for 20 years. Bielawa eventually resurrected Vireo as part of her residency at Cal State Fullerton’s Grand Central Art Center (GCAC) in Orange County in 2012.

Opera for the Netflix generation

The idea to write an opera in episodes as one might approach a sitcom or telenovela came from Netflix. Specifically, the TV series Arrested Development, which Bielawa loves for its lampooning of life in Orange County’s Newport Beach with absurdist wordplay and dark wit.

In the summer of 2012, when Bielawa and GCAC director and chief curator John Spiak were casting around together locally for a new project, the pair realized they were both fans of Arrested Development, and Spiak reminded Bielawa that the series takes place in the Orange County area.

“I looked around me and realized that one way to make innovative work that engaged with the community was to recognize that many of the smartest and most creative people around were involved in this evolving new form,” Bielawa says. “The way to make an opera that was native to SoCal was to embrace its flagship format, the episodic series.”

Taking TV opera in a fresh direction

Opera on television is nothing new. Gian Carlo Menotti’s beloved Amahl and the Night Visitors was specifically composed for NBC in 1951 as a Christmas special, and Benjamin Britten’s less well-known Owen Wingrave was composed for television broadcast on the BBC some 20 years later.

Running at almost three hours — if you were to watch all 12 episodes back-to-back, that is — Vireo is just about the same length as the average opera. (Or it will be, once the project is finished, which is expected to happen before the end of next year.) But unlike the other two televised operas mentioned above, which are still occasionally performed on stage, Vireo doesn’t fit into a traditional live opera setting. The episodic piece takes place in multiple time periods simultaneously. This time-bending is quite tricky to represent in a live performance. Also, Vireo features a dizzying number of collaborators like the Kronos Quartet, the American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME), the Bay Area choral group Cappella SF, and even a marching band from a high school in Indio.

What the episodic, web-based format of Vireo does provide for fans of opera is choice: the viewer can decide to snack on a single episode, take in a few at once, or binge-watch the whole thing in one go. “Each episode stands alone as a work of art, and yet also presents itself as part of a larger narrative,” says Otte, who worked on the globe-trotting remount of Philip Glass’ seminal opera Einstein on the Beach. (The production made a stop at Cal Performances in Berkeley in Oct. 2012.)

Success not a given

As with all operas, there are a lot of moving parts and production costs are often high. The budget for Vireo is $600,000. Although the project receives funding from a few foundations and grant programs (most prominently the community television organization KCET and Grand Central Art Center), Bielawa and her team still need at least $260,000 to make it through to the end of the series. And success is certainly not a given. According to a 2015 study conducted by the opera industry organization Opera America, of the nearly 600 new operas premiered over the past two decades, only 11 percent have received a second production.

As a web-based work released in serial format, Vireo faces its own specific set of challenges. For one thing, the technical and artistic hurdles of producing a serialized opera with tons of collaborators in unusual locations like Alcatraz are immense. Then there’s the esoteric, highly brainy subject matter: the (mis)treatment of female hysteria is hardly the stuff of an evening’s light entertainment. It remains to be seen if the characters manage to connect with the video audience, many of whom may be viewing the episodes on the shrunken screens of laptops, tablets and even smartphones.

But Bielawa is fearless and clearly has talent. Vireo has already won a major prize from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers Foundation (ASCAP), a professional membership organization of songwriters, composers and music publishers, for its curious hybrid structure.

But Vireo isn’t just a point of innovation for an art form that has long struggled to stay relevant. Bielawa is one of very few successful female opera composers in a field dominated by men. As such, she is aware that her work is also unusual in content; her heroine is not simply an exotic Carmen or Madame Butterfly. “I’m working with these very young women who are playing these important and complex lead roles,” Bielawa says. “One of my motivations is to insist on roles for women in opera that have depth and breadth of character.”

Watch the first two episodes of Vireo:

This article was originally published on https://www.kqed.org/arts/11752576/an-opera-for-the-netflix-generation-filmed-on-alcatraz

* Notes *

* Notes *

My feature about Lisa Bielawa's made-for-television opera Vireo is up on KQED Arts.

* Tattling *

This was my second visit to Alcatraz in two years, which was very funny to me since I had lived in the Bay Area so long before ever going.

Was pleased that I knew one of the singers involved in the filming and had someone to discuss the San Francisco Opera season with on the ferry.

* Notes *

* Notes *

My review of San Francisco Opera's Jenůfa up on KQED Arts.

* Tattling *

A very enthusiastic couple were in Row L Seats 13 and 15 of the orchestra level. At least one of them was crying during the performance and they were among the first to stand during the ovation. They screamed "bravo," "brava," and "bravi" at every opportune moment. Normally I hate hearing the audience during a performance, but something about their love of opera made it not bother me.

THE DO LIST

By Charlise Tiee Jun 16, 2016 | Updated Jan 11, 2024

Malin Byström in the title role of Jenůfa at San Francisco Opera. (Photo: Cory Weaver)

In the wake of a fascinatingly gritty Carmen hampered by lackluster singing and a Don Carlo that counterbalances a great cast against boring staging, San Francisco Opera saves the best for last with a brilliant production of Czech composer Leoš Janáček’s Jenůfa, which opened Tuesday night.

Jenůfa is a tour de force, with sublime musicianship from the orchestra, a sleek triangular set, and above all, a cadre of world-class singer-actors.

Janáček’s most popular opera, first performed in 1904, takes place in a Moravian village in the 19th century. Like numerous other operas of the era that focus on unfortunate damsels (La Bohème, Tosca, Madame Butterfly…) its narrative follows the fate of a lithe, young woman whose life gets upended when she sleeps with the local miller’s ne’er-do-well son, finds herself pregnant out of wedlock, and then has to deal with her stepmother’s wrath.

The composer’s music involves a complex interplay of orchestra and vocal lines, punctuated by lots of whirling rhythms. There are many moments of gorgeous lyricism, too. In Act II, perhaps most notably, Janáček writes gorgeous, harrowing melodies for Jenůfa’s stepmother, Kostelnička, that draw out the complexity of the tough-minded yet tortured character upon whose extreme actions much of the ensuing plot-line is built.

San Francisco Opera’s production, directed by Oliver Tambosi, features a large stone, center stage. The ponderous rock first emerges from the ground, then dominates the stage in Act II, and is finally broken up pieces in the last act. Granted, the symbolism is way too obvious, as when the drugged Jenůfa sings of her head feeling like a stone in the second act. Yet the poetically abstract set design looks elegant without being slavishly descriptive.

The work takes fire from the very first moment, with Czech conductor Jiří Bělohlávek leading the orchestra with fluid transparency. Most of the singers seem well matched to their roles. Malin Byström is an ideal Jenůfa. Her mellow soprano is clear, and the character’s journey from frivolous, sweet girl to scarred, damaged woman comes through the performer’s entire being, both in her singing and her physicality.

Karita Mattila is frightening as Kostelnička, the stepmother whose terrible crime to save her reputation is pivotal to the work. Mattila’s voice is special; it has a creamy heft to it, yet sounds bizarrely ethereal as well. Mattila’s portrayal makes Kostelnička seem human despite her savage side.

The production is David Gockley’s final offering as San Francisco Opera’s general director. It makes for a memorable curtain call.

Jenůfa runs through Friday, Jul. 1 at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco. Tickets and information here.

This article was originally published on https://www.kqed.org/arts/11691653/sf-operas-jenufa-a-memorable-curtain-call-for-david-gockley

Leave a comment